Struggling to achieve the American Dream? It’s out there. Just in another country.

When someone references “the American Dream,” one is often reminded of something we were taught about in elementary school. When learning about immigration in the third grade, we were taught that people were immigrating to the United States to chase “the American Dream.” The image put in our head was a husband and wife, living in a small, simple house in the suburbs, with two to three children, and perhaps a dog. These houses came with green, lush, well-manicured lawns and white picket fences. The image included the idea of the mother being a housewife, as the father — the “breadwinner,” per se — worked a job that paid well enough to allow him to be the only one that needed to work.

In the theater department, we read plays of many different genres, of many different styles, and from many different countries. From Ancient Greece, to medieval France, all the way up to recent productions on- and off-Broadway, I have read many plays thus far in my college career.

My junior seminar focused on American drama and American playwrights. These included people such as Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams and Lorraine Hansberry. Most all of these American dramas deal with the idea of “the American Dream.” Given this, and my own experience living in the United States for 21 years, I can confidently say that the American Dream is a dead, outdated concept that barely existed in the first place and was created to keep Americans happy about working for money-hungry corporations.

The first issue I have with “the American Dream” still being used as a viable term is that it is not the same for Black, Indigenous and People of Color as it is for white people, both historically and in today’s world. The modern-day definition of “the American Dream” was born in the mid-1950s, during the rise of post-war consumerism. As women returned to being housewives from their wartime factory jobs, advertisements for household appliances quickly changed their targets to the idealized post-war American family. In this image, we have the hardworking man who earns all the money the house needs, the housewife who has all of the best appliances that she needs to be the perfect spouse, and children that play sports and need to eat picture-perfect meals every day of their lives.

What this image does not have, and did not ever have, was a BIPOC family in the same scenario. This is because “the American Dream” sets an inherently racist expectation, one that focuses on the “perfect,” white American family that BIPOC folk should assimilate to. It effectively disregards the existence — and therefore, importance — of families of color.

One could argue that the reason this was never depicted was because BIPOC families did not live that way, and they would be correct. Families of color did not live idyllic lives due to the systemic racial inequality they have faced throughout history. “The American Dream” has never been a privilege extended to persons of color, and that is certainly seen in both post-war consumerism as well as modern-day America.

The main reason “the American Dream” is dead for all Americans, regardless of race, is due to wealth inequality in the United States today. As the world has become more evolved, more jobs require education further than high school. Much to the working class’s disadvantage, the cost of higher education has disproportionately risen in comparison to the income of average Americans. This makes a college education much harder to achieve for people from lower-income families.

One must also consider what it currently means to be a “middle-class” family in America. With the general range of the “middle-class” status being between $45,000 and $130,000, and the median American income being approximately $30,000, it is clear to see that most families who manage to fall into the middle or lower-middle class are closer to the poverty line than they are to achieving upper-middle class status (at approximately $140,000 to $150,000).

Furthermore, the generational gap between then and now is exceptionally wide. While it was perfectly viable for a person just out of high school to pay for their college education by flipping burgers for $4 per hour, that is not the case today. Inflation has increased at an alarming rate, while the national minimum wage has not. In Pennsylvania, the minimum wage is $7.25 per hour. In Crawford County, this is the standard most any job will start you at, although some will bump you up to $7.75-$8 per hour if you have previous experience. But for a young person who has never worked before, the prospects are grim for the amount of money they will be able to make in a single summer.

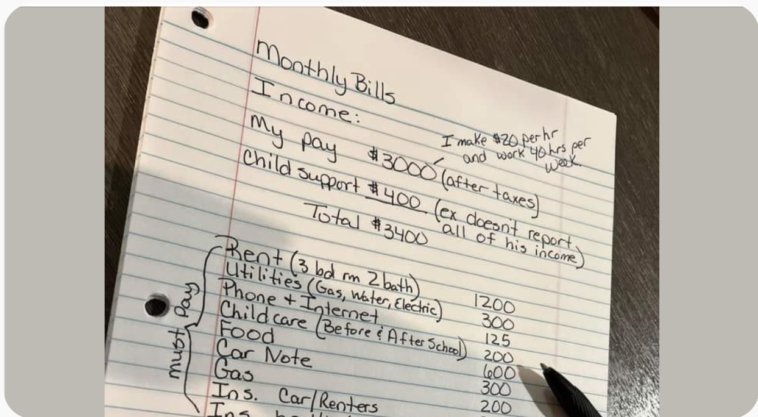

I am thankful to have one of the few well-paying hourly summer jobs in Crawford County. I started at $8.50, given my experience working for minimum wage the previous summer at a farm market and now make $10 per hour. Each paycheck, I made around $450-$500. After working for approximately 12 weeks (June through August), I’d made around $3000 for the summer. My monthly bills come to approximately $75. Already, one-third of my total summer income is going to be spent on bills. The remaining $2000 is less than one-tenth the cost of tuition alone in a single semester at Allegheny College, and for comparison, approximately over one-tenth of the average yearly cost of attending Edinboro University. Unfortunately, my summer employment situation seems to be unique compared to the majority of students on campus. It is absolutely no longer possible to pay for a college education with a summer job alone, and “the American Dream” only perpetuates the idea that it is.

The same idea applies to the millennial housing crisis; the cost of owning a home is almost 40% higher than it was in the 1980s, which is around the time the later boomers were finishing college. We can no longer afford the lives our parents led, or the lives their parents led during the birth of “the American Dream.”

On the same level, “the American Dream” is something commonly used by today’s older folk to berate and belittle millennials for their financial instability. The idea that a person who works a full-time job 40 hours a week, with benefits, can be totally financially stable is a fallacy we need to stop perpetuating. It is by no means possible for every American because of racial inequality, gender inequality and a lot of other things that cause people to be stripped of any chance at “the American Dream.”

In countless plays I have read since coming to college, families are torn apart by “the American Dream.” Some struggle to find housing, some struggle to find identity, others struggle to find employment. The worst part is that these plays primarily take place in the mid- to late-twentieth century, between 1950 and 1999. “The American Dream” has never been real for most Americans, and instead, has served as an unachievable standard for generations, for people of all backgrounds. It is a concept that I despise, and that I am tired of hearing used by older generations as a reflection of their relative success in attaining this unrealistic ideal, as if proof of their superiority. Its goal was the promotion of consumerism and capitalism as a societal norm, and sadly, has reached past this goal and still seeps into our lives half a century later.